Over the course of my career, digital identity has applied to many things in an enterprise context. First it was the network, then the device, then the user. And just when organisations got used to, and good at, managing workloads, service accounts, and APIs as “first-class citizens”, AI Agents emerged.

If you've been to a tech conference recently, or have managed to not live under the proverbial rock, you’ve heard the term tossed around a lot lately. Vendors are embracing it, management is overusing the term and engineers are (supposed to be) experimenting with it. You probably have someone at your organisation ask you recently if you’re “using agents yet.” And yet, there’s surprisingly little clarity on what an AI agent actually is, let alone how it should be governed, secured, or identified.

What Is An AI Agent?

Depends on who you ask.

Despite the growing interest, there’s no consensus on what counts as an AI agent. Here’s a rough spectrum of current interpretations as I understand it:

Views on AI Agents

The challenge isn’t just semantic. Each of these interpretations implies very different identity and security requirements.

If an agent is just a stateless function call, maybe you audit the prompt and call it a day. But if it’s an entity that operates over time, remembers context, and initiates actions across systems? That’s not a chatbot. That’s a user you didn’t hire and you very likely won't have full oversight of it. You might want to apply strict governance protocols to it as it snakes its way through your organisation.

Worse, most enterprises don’t yet distinguish between these types (mostly because I don't know of or work with a client that has actually thrown an AI Agent into their organisation just yet). There’s a risk of flattening all AI agents into “non-human identities” and assigning them the same governance as a Terraform script or Slack bot. If you're after just checking a box, that's cool, but it will likely become a headache down the line.

Is An Agent A Glorified Service Account?

It's quite tempting to handle new and emerging concepts by mapping them to older concepts. When APIs proliferated, we gave them service accounts. When bots showed up in business processes, we registered them in the IAM stack like users and called them machine identities. When cloud workloads emerged, we invented workload identity. AI agents will likely be no different.

Faced with unfamiliar behaviours and ambiguous definitions, most orgs will default to what they know: wrap the agent in a generic machine identity, assign it to a system, and Bob's your uncle. It will get an account, some roles, some documentation and if you're lucky, someone remembers to rotate its API key.

Unfortunately, agents aren't just executing logic — they’re interpreting intent. They’re ingesting data, making decisions, and sometimes taking action in ways that aren’t fully transparent to the humans who invoked them.

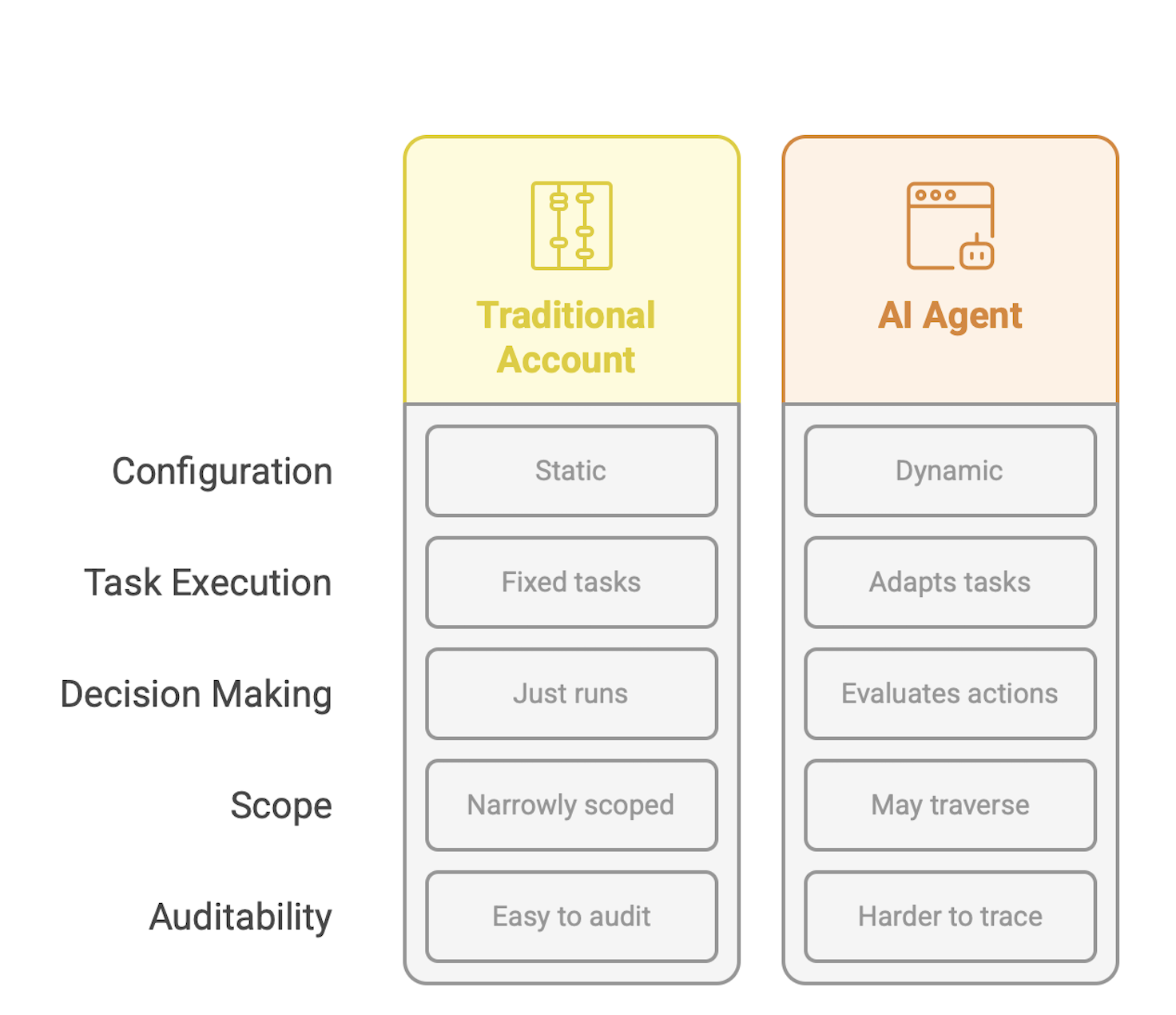

Traditional Service Accounts vs Agents

From a security perspective, this creates a troubling blind spot. When something goes wrong like say, a leak, a breach or a misfired account termination, you’ll be left staring at an audit trail that says “Agent Smith did it.” But not why, or on whose behalf or with what justification. You'd be lucky if Agent Smith were even still around; after all, agents can be ephemeral depending on what they're meant to do.

So What?

All this begs the question - are our existing identity stacks still fit for purpose?

I have to admit I'm still coming to terms with what a solution to all this will eventually look like. If AI agents are going to become routine actors in the enterprise, our IAM systems will need to evolve well beyond where they are today. Not in the sense of adding another checkbox or creating an “agent” user type. That would be like bolting a sidecar onto a moving train. What’s needed is deeper: a rethink of what identity means when the actor is no longer human or even fully deterministic.

I'm almost certain that we'll see the likes of SailPoint, Okta, Saviynt and others start to address some of these problems in the coming months. Microsoft’s already partnered with ServiceNow and Workday on this front. At the very least, we'll need to look at the following:

Creating new identity constructs that are more expressive than a service account and more ephemeral than a workload identity.

Audit actual prompts that make agents do what they do - perhaps rethink privileged accounts?

Include agents with the remit of workforce identity governance

Keep humans in the loop when it comes to making decisions on what agents do

Of course, none of this matters if AI Agents don't take off in a meaningful way within enterprises. But if they do, I'm guessing our identity systems will need to do a whole lot more than just manage access.

———

Postscript:

I used ChatGPT and Claude as a ‘thinking partners’ while developing this piece and am likely to use this method for future posts. It helps me test arguments, identify gaps in logic and explore alternate views. I also used napkin.io for creating the included diagrams. Farhad Manjoo’s take on how he incorporated GenAI into his writing workflow is a useful listen and somewhat similar to how I’ve started using these tools.

Additionally, I drew on some excellent writing that touches on the evolving nature of agents, identity, and AI systems:

Arvind Narayanan & Sayash Kapoor – AI as Normal Technology

Microsoft – 2025: The Year The Frontier Firm Is Born

Benedict Evans – Looking For AI Use-Cases

Identity Defined Security Alliance (IDSA) – Managing Non-Human Identities (2021)